|

|

|

I first met Rachel Bronson two years ago when I joined a small team in Chicago to help launch the Arts Science Initiative for The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. For over 70 years, The Bulletin has been bringing together science leaders, policy makers, and the public to address global existential threats. The goal of the Art Science Initiative is to create a powerful platform where artists can present their work, interact with scientists, develop new ideas at the intersection of art and science, and engage new audiences committed to solving the globe’s most urgent issues.

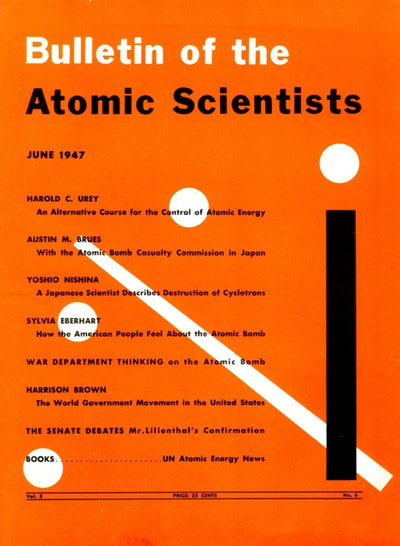

In her role as President and CEO of the Bulletin, Rachel oversees publishing, the Doomsday Clock, and activities around nuclear risk, climate change and disruptive technologies. She was previously on the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, an adjunct professor at the Kellogg School of Management, and served as senior fellow and director of Middle East studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. Her book, Thicker than Oil: America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia (Oxford University Press, 2006), has been translated into Japanese and was published in paperback in June 2008. Her writings have appeared in publications including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The National Interest, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Huffington Post and The Chicago Tribune. She has appeared as a commentator on numerous radio and television outlets, including National Public Radio, CNN, al Jazerra, the Yomiuri Shimbun, “PBS NewsHour,” “The Charlie Rose Show,” and “The Daily Show.” Rachel has served as a consultant to NBC News and testified before the congressional Task Force on Anti-Terrorism and Proliferation Financing, Congress’s Joint Economic Committee, and the 9/11 Commission. Bronson was named by Today’s Chicago Woman magazine as one of 100 Women to Watch (2012), 20 Women to Watch by Crain’s Chicago Business (2008), a Carnegie Corporation Scholar (2003) and a Glamour Magazine “Wow Woman” (2002). We recently reconnected in Santa Fe to continue our work on the Arts Science initiative with a team of talented artists, makers, and creative thinkers from Santa Fe. Here are three questions for Rachel Bronson. QUESTION 1: One of the most recognizable aspects of The Bulletin is The Doomsday Clock an iconic image created in 1947 to visually depict the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe by nuclear war and climate change. Midnight is global catastrophe, we are currently at 2 minutes to midnight. The Bulletin garners the attention of scientists, politicians, diplomats, and organizations such as the United Nations. The Clock has also recently captured the attention of popular culture—including such iconic political satirists and popular news shows as Steven Colbert, Whoopi Goldberg, and TMZ. As a result, some of the most intractable and vexing issues of our time are accessible to much wider audiences globally. What is it about The Doomsday Clock that makes it so accessible, and why do you think it has the ability to capture the attention of audiences far beyond experts in the field? The magic of the clock is that it is blunt and deceptively simple. It boils down a tremendous amount of expert information about existential threats into one basic number, the time on the Doomsday Clock. The creator of the Clock, Martyl Langsdorf was married to a Manhattan Project physicist, and she spent time with the leading scientists and civic activists of her time. She understood at a gut level that her scientist husband and his scientist friends were desperately concerned about science and technology’s advancement, and its ability, for the first time ever, to alter the future of humanity. These scientists were looking for ways to engage the public about the revolutionary changes that were underway, and get their help in demanding responsible global policies to keep us safe. Martyl poured all of this into her image. Those scientists also understood that they alone couldn’t mobilize the public and convey the urgency they felt. They could publish the best and smartest articles, but if no one read them, it wouldn’t matter. They were smart enough to understand art’s power, and to reach out to Martyl to design a cover to their magazine. And boy did she deliver. Her clock conveyed the sense of urgency and agency that they were looking for. Readers suddenly understood that they could turn back the hands of the Doomsday Clock, but they had to act quickly. In 1949, in response to the Soviets testing their first atomic weapon, the editor of the Bulletin, Eugene Rabinowitch, moved the hands of the Clock forward from 7 to 3 minutes to midnight, making Martyl’s static design dynamic. 71 years after it first appeared, the Doomsday Clock has moved 23 times, and has captured the public imagination. In its blunt simplicity, it allows everyone and anyone to join a conversation about whether or not we are today safer or at greater risk than we have been across the past seventy plus years we have been moving the clock. Today, the clock time includes not only nuclear risk, but climate change and other disruptive technologies. That is because our board believes that you can’t answer questions about the future of humanity without considering such issues. Technology has evolved since 1947, when nuclear risks were the only existential threat. We have a lot more information about the Clock on our website at https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/ QUESTION 2: As I mentioned in the introduction, the Bulletin has been building an Arts Science initiative over the past few years. We now understand that the arts are a critical point of access to much wider audiences, to broaden channels of communication, and to drive change through the power of numbers. What have been some of the biggest challenges you have faced in integrating the arts into your work at the Bulletin? The Bulletin has been able to attract science and policy experts from around the world who work on existential threats. It is possible to attract such expertise because we’ve been working on this issue for over 70 years. Back in the day, we would receive submissions from artists from around the world as well to appear on our cover as well as in our pages. We lost many of these connections and our internal expertise when we went digital in 2009. With our new Arts Science Initiative, we intend to reintroduce the arts into our offerings because in this highly digital world visual imagery has the power to engage and mobilize, and the future of our planet demands nothing less. However, we also have to be very careful that whatever art we publish is as technically sophisticated as our existing contributions. Therefore, we are building out our network to connect with recognized arts leaders to help us identify leading talent that is working responsibly on our key issues of nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technology. We want to connect them with our scientists to also ensure that their art is scientifically grounded. Building the arts expertise to match our existing scientific expertise is not straightforward, but I am confident that we will get there. The arts expertise exists, we just need to find it and connect with it. QUESTION 3: When artist Martyl Langsdorf created the Doomsday Clock, one of the most compelling and critical aspects of this project was the connection between the arts and sciences. We have spoken at length about this connection, and how the arts can be engaged to disseminate these issues to much broader audiences. Why do you believe that now, more than ever, art is critical point of access to disseminate messages, build audiences, and ultimately tip the power balance to drive change? We know that images and stories captivate broad audiences, and can amplify the work of leading experts. We all know that the movie Dr. Strangelove helped generations of viewers experience at a gut level the dangers and absurdity of the nuclear arms race. What many might not know is that Stanley Kubrick got his idea for Dr. Strangelove from an article he read in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The power of the film is that it’s a great film, but also that it rests on significant technical expertise, and a pretty deep understanding of nuclear strategy. Powerful art is not created in a vacuum. It often draws on a tremendous amount of technical knowledge, in addition to a keen sense of the political issues of our day. This is why we are delighted by the Take Back the Clock exhibit now on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We worked closely with them in developing it, to provide a hands on experience for a new generation to engage on issues of nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies. Also we worked closely with new media artist Ellen Sandor to create a virtual reality tour of the Doomsday Clock using Martyl’s color palette and iconography. Today, I believe we are in serious need of new images and expressions not only around nuclear risk, but climate change and particularly disruptive technologies. There are huge ethical questions facing us right now around gene editing, artificial intelligence, and cyber to list just a few. We know, that science’s advancement will bring huge benefits. It will raise millions out of poverty, advance health care and quality of life, and extend lifespans. But we also know it brings great risks. It will threaten the employment of millions, has the potential to create designer babies and undermine democracies. I firmly believe that science is neither good nor bad, but both. It’s the public policies that we bound it with that will tip the balance about whether it’s on balance helpful or harmful. BONUS QUESTION: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? I find the work of Jennifer Doudna quite fascinating as I do the Partnership for Artificial Intelligence cofounded by Bulletin Board of Sponsors member Eric Horvitz. Jennifer is a leading developer of the gene editing technology CRISPR. Her scientific breakthroughs are leading to enormous advancements in healthcare, and someday may help us cure cancer and genetically-caused diseases. However, Dr. Doudna is also quite concerned about the ethical questions that has surrounded her gene-editing tool. She and some of her colleagues have called for a worldwide moratorium on the use of CRISPR until scientists, ethicists and the public fully understand the issues surrounding its breakthrough. I am in awe of her position. She is clearly a huge advocate. She invented the technology. But she also understands better than most what is at stake. This kind of ethical struggle is exactly what the Manhattan project scientists experienced, and is why they got as engaged in politics as they did. I find Jennifer Doudna’s concerns a direct extension of the kinds of issues the Bulletin has been doing for more than 70 years. I also find fascinating the Partnership for Artificial Intelligence (AI). The partnership is made up of leading pioneers in the field of AI. Like Doudna, they also recognize that artificial intelligence has the potential to bring benefits but risks as well. Participants are trying to better understands the risks of AI so that we can build better policies that will allow us to avoid its risks, while leveraging all the benefits it will bring. There are important similarities between what Doudna and Horvitz are doing, even though their fields of synthetic biology and artificial intelligence are quite different. Both are advocates for science’s advancements. Both realize that the public needs to get engaged to advocate for good public policy. At the Bulletin, we hope that our arts science initiative will provide new ways to understand all the benefits and the risks, to engage the public to advocate for a safer future.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed