|

|

|

Ndaba Mandela was born with a daunting charge – to follow in the tremendous footsteps of his grandfather, Nelson Mandela. His new memoir, Going to the Mountain, provides an intricate, tender, and surprisingly candid account of what it was like to be raised by his iconic “Granddad.” Ndaba’s upbringing came with privilege, but also with demands that could feel rigid and stifling—and he frequently pushed against the incredibly exacting standards set upon him. Over the years, however, Ndaba grew into the leader that he is today. He now travels the world to spread the Mandela Legacy and help motivate young people to become the change they wish to see in the world. He is the co-founder of the Africa Rising foundation, an organization dedicated to catalyzing a new wave of young Africans who will empower themselves to be at the forefront of Africa’s development. Ndaba was recently named one of the “28 Men of Change” by BET. I had the extraordinary opportunity to spend time Ndaba Mandela through a partnership with World College, USA. Together, UWC-USA’s President Dr. Victoria J. Mora and I posed these three questions to Ndaba Mandela. QUESTION 1: How do we get out from under the weight of our own histories–personal, political–while still learning from that history? Well the trick is to try and establish yourself outside of what your parents or predecessors have done. This does not mean we have to do something different. However, it’s important we create our own value, our own image and own credibility, basically our own story. QUESTION 2: What three habits do you think are crucial to becoming “master of your own destiny”? In order to be the “master of your own destiny” you have to be doing something you are passionate about. You need to dedicate yourself at least 4 times a week to building your own brand. Your destiny is where you want to see yourself say when you are 50 years old or at least 45 years old. Someone said to me once you turn 35 that’s what you become known for. I don’t agree 100% QUESTION 3: How do you reconcile progress and cultural traditions? Are they at odds? No, I don’t believe they are at odds. You can still keep your traditions and have progress in your own life. You can still be a proud African and be a global citizen at the same time. I value my language, my customs, but I’m able to travel to the world and raise awareness for the challenges our people face in our impoverished communities in Eastern Cape. We fundraise so that young people can learn about computers and how they can access information and help them understand the bigger world around them. Bonus Question: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? Social Entrepreneur, Zuko Mandlakazi, on his innovation in helping the deaf community. I choose him because he is from my province of the Eastern Cape – The Home of Legends. He’s my home boy who is deeply rooted in Eastern Cape, and is proudly South African.

2 Comments

Originally from Siksika Nation in Alberta, Canada, Amber-Dawn Bear Robe is a curatorial phenomenon. She holds MA’s in both American Indian Studies and Art History and is currently Assistant Faculty of Art History in the Museum Studies department at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her latest curatorial projects range from organizing the annual Contemporary Indigenous fashion show for the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA) to curating an exhibition for The Tweed Museum in Duluth, Minnesota titled Blood Memoirs: Exploring Individuality, Memory, and Culture through Portraiture. Oh, and she’s also a DJ. Amber-Dawn is constantly challenging the assumptions and stereotypes of the representation of Indigenous voices in the contemporary arts scene—how Native Art is curated, studied, and presented to the world. Here are three questions for Amber-Dawn: QUESTION 1: 2019 will be your fourth year designing, curating, and producing the Contemporary Indigenous Fashion Show in conjunction with Santa Fe’s Indian Market, SWAIA. Around for 96 years, SWAIA has successfully attracted visitors and collectors from around the world to experience, explore, and purchase traditional Native American Arts. Your fashion show is bold, transcendent, and presents a wildly different perspective on what Native American Art looks like, and how it can be presented to a global audience. Why you are drawn to Indigenous Fashion, and why shake things up at a traditional event like SWAIA? This will actually be my sixth year producing the SWAIA fashion show (Southwestern Association for Indian Arts). The first one was in 2014 at Cathedral Park on the Santa Fe plaza. When I first moved to the area, Pasty Phillip, the Director of the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, (MoCNA) asked if I could organize a fashion show for the museum in 2013, which I titled Fashion Heat. I saw this as an extension of being an art curator, so I said yes, and I have been organizing fashion shows featuring Indigenous designers ever since. I ended up creating two fashion shows for MoCNA. The second one was held at the El Dorado hotel, in partnership with, and during the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival. The event included the work of Wendy Red Star, and vintage Lloyd Kiva New designs. I next approached SWAIA about producing a fashion show for the annual Market and the show garnered instant attention, becoming greatly popular, and one of the most anticipated and attended events of Market. The first show was done with virtually no budget, with all involved (models, designers, hair & makeup etc.) donating their time and talent. The fashion component of my career organically happened, fell in line with my background, education about, and experience with contemporary Indigenous art. My goal is to always incorporate a contemporary artistic component to any event, leading to diverse, exciting and vibrant programming. Including any fashion events I produce for SWAIA. SWAIA has a long, complex history, one of exclusion and inclusion, historically based on non-Indigenous values. Of course this has changed since 1922, but the complexities are still present. My goal is to side step these dated rules and regulations. My ambition with any fashion show I work on is to feature designers who are not bound by conventions or expectations of what “Indian” art or dress is or should be. The goal is to support and foster Indigenous expression free from rules and regulations that have been placed on Native North American artists since contact. QUESTION 2: Beyond the runway, your museum exhibitions question the traditional boundaries and assumptions of how Indigenous art and culture are defined and displayed. You once stated that “Contemporary Native art pushes the boundaries of what Native people, and art, are about.” Can you speak about pushing those boundaries, and why your career has been largely comprised of challenging traditional assumptions about Indigenous arts? Indigenous art in Canada is a much different scene compared to the United States. For example, there is a vibrant artist-run-center community in Canada that does not exist to the same extent in America. Artist-run-centers support a significantly different artistic expression, voice not driven by a consumeristic art market. Art not restricted to concerns of “will this look good over someone’s couch” or “does this look Indian enough” leads to exciting artistic discourse that often challenges a viewer. Artist run spaces embrace Installation, performances, video art, mixed media work addressing present issues in political and social areas, raising awareness about excluded or marginalized histories and serve as a platform form of self-representation. Visual and creative sovereignty that exceed viewer expectations or stereotypes. Non-Native people still love the “Edward Curtis Indian,” a statement coined by Vine Deloria. Generally, people in America know very little about the history of the country they live in. Including that this is all Indigenous land, stolen though the mass genocide of Indigenous people, their resources and aggressive assimilation programs. Artists bring attention to histories such as this when it is not controlled by art markets, collectors and commercial galleries. Artist are vital to a strong and healthy community. QUESTION 3: So with fashion, teaching, the arts, and music you have your hand (and brain) in a bit of everything that is Indigenous arts and cultural. What is next on your horizon? What is the most pressing need you see that you would like to tackle? Being in the arts can mean wearing many different hats. For me that entails hosting events, continual research, keeping my finger on the pulse of the current art scene, preparing lectures, marking essays, writing essays, while making time for studio visits, grant writing and fundraising. Which bring me to two most pressing projects. Currently, I am working on the 2019 SWAIA Fashion Show, including cultivating funds for the event. My goal is to bring an amazing New Zealand fashion designer, Shona Tawhiao, to show this year. $3000 needs to be raised to get her here with her fabulous and intricate designs. If anyone reading this would like to sponsor her travel please contact me. A second immediate project is establishing a Satellite space in Santa Fe for Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art, the largest Indigenous artist run center in North America. This endeavor has recently been realized with the satellite Urban Shaman (US) launching in Vital Spaces, another venture I am involved with. I am working with the current Urban Shaman (US) director, Dania Warren, on the first US programming featuring Cree/Metis artist Kevin McKenzie in April 2019. Bonus Question: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? There are many Indigenous artists and curators doing amazing, innovative work right now. Currently Jeff Gibson and Kent Monkman are showing at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (MoCNA), in the exhibition Art for a New Understanding: Native Perspectives, 1950s to Now. Another artist who I have admired since the 90’s and who is always doing remarkable work is Rebecca Belmore. She was the first Indigenous woman to represent Canada at the 2005 Venice Biennale. She is also one of the first artists to address murdered and missing Indigenous women in 2002 with her performance titled Vigil, performed in the downtown lower eastside of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. So much more can be discussed in terms of how the three artists just mentioned are some of the most interesting artists, creating disruptive work addressing issues such as identity, gender, colonialism, politics, and Indigenous histories. So much HAS been written about these artists. I encourage people to visit the current exhibition at MoCNA to visit the links embedded in my responses. As a covert CIA agent, Valerie Plame dedicated her career to protecting America’s national security and preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and managed top-secret programs to keep terrorists and rogue nation states from acquiring nuclear weapons. Her life garnered international attention when her career came to an extremely dangerous and abrupt halt when she was publicly unmasked in July 2003 after members of the George W Bush administration leaked her identity to the press. She became an international celebrity when in 2007 she wrote the New York Times best-selling memoir Fair Game: My Life as a Spy, My Betrayal by the White House that was subsequently released as a major motion picture starring Sean Penn and Naomi Watts. (Yep, she actually looks like Naomi Watts.) She has since written fictional spy thrillers Blowback and Burned, is regularly featured and interviewed on national and international media. Valerie has also been an incredible asset to Creative Santa Fe; was instrumental in our Disruptive Futures: Nuclear Weapons Summit last year; and is an trusted advisor, mentor, and friend. She is currently organizing the conference “Spies, Lies & Nukes: Inside International Espionage," November 3-4, 2018 to bring together experts with extraordinary experiences and access to the highest levels of US policy-makers. For more information and to register: www.spyseminars.com Here are three questions for Valerie Plame: QUESTION 1: Since being outed in 2003, you have become an important advocate for non-proliferation along with celebrities like Jack Black, Morgan Freeman, Queen Noor of Jordan, and Warren Buffett. Can you speak a bit to why it is important to leverage art, music, theater, pop-culture, and even celebrity to increase public awareness and incite calls to action on this critical issue? We are a celebrity obsessed culture and if those who believe that the world would be better off without nuclear weapons can leverage the arts – and the celebrity culture – to amplify that message, then all the better. By their very nature, nuclear weapons are scary, intimidating, and complicated. Many people will simply shut down and not even think through the issues when you mention “nuclear weapons” because it all just seems too hard. What the arts can do in this realm is provide another access or entry point into the discussion; one that is not quite so fraught with fear. That’s why Creative Santa Fe’s Disruptive Futures: Nuclear Weapons Summit gathering was so revolutionary: it took on a topic that is generally reserved for academia or highly specialized gatherings and blew it wide open. You didn’t have to be an expert to comment and consider the proliferation of nuclear weapons which threatens all humans with extinction. QUESTION 2: In an interview with The Guardian you said “In popular culture, female agents are usually either highly sexualized or hugely physical – it is either using a sequined dress or a gun. But actually the most important weapon you have is your intellect.” Vanessa Pierson, the protagonist in Blowback and Burned, is clearly so much more than the two-dimensional and highly sexualized spy characters of the past. Why is it important, now perhaps more than ever, to feature strong, courageous, intelligent, and powerful women in your work? When stereotyping occurs, whether gender, racial, or religious it is detrimental to all of us because it fails to take into account—or encourage—the spectacular contributions we can make to our world, regardless of our sex, color, or religion. Mountains of research confirm what we have long suspected but not acted on very successfully: better solutions and organizations almost always come from a more diverse set of minds and experiences working on problems. The sexy female spy is a worn troupe that I thought deserved to be tossed out. Why can’t we have a smart, complicated, and yet feminine spy? That was the inspiration behind Vanessa Pierson. The #MeToo movement is an important next step in making sure that more voices are heard and taken into account. This is the moment to celebrate strong, courageous, intelligent and powerful women! QUESTION 3: One of the important lessons we learned in hosting Creative Santa Fe’s Disruptive Futures: Nuclear Weapons Summit is that the topic is so daunting, complex, and politicized that most people feel they could not possibly make a difference. What are ways that people concerned about nuclear weapons can get involved and have agency to make an impact? I agree with this assessment; that an individual faced with the vast international nuclear weapons questions can feel helpless. But giving up or turning away is not the answer. The first step is to begin to understand the issues. I highly recommend the on-line courses offered by the williamjperryproject.org as a place to start. This organization was started by former Secretary of Defense William Perry to engage and educate the public on the dangers of nuclear weapons in the 21st century. It’s accessible, thorough, and really well done. The other way we make changes in our society is through our elected officials. Find out what—if anything—your representatives say about nuclear weapons. Then, act accordingly. Bonus Question: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? Given the state of our politically polarized nation and the abundance of “fake news” and its attendant threat to democracy, perhaps some of the most important and disruptive work being done today is genuine investigative reporting from nonpartisan sources. I am a big fan of ProPublica.org for its efforts to “…expose abuse of power by government, business and other institutions and to spur reform thorough the sustained spotlighting of wrongdoing. Hakim Bellamy is a national and regional Poetry Slam Champion, an educator, author, and the inaugural Poet Laureate for the city of Albuquerque, New Mexico. He facilitates youth writing workshops for schools, jails, churches, prisons and community organizations in New Mexico and beyond, and is the Deputy Director of Cultural Services for the City of Albuquerque.

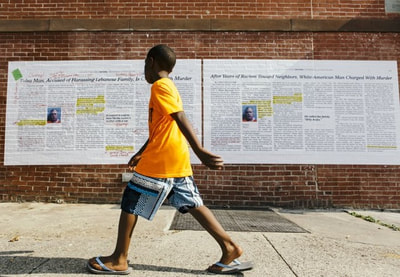

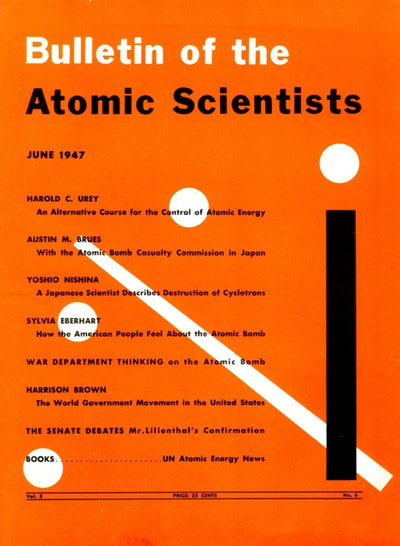

Hakim co-founded the multimedia Hip Hop theater production Urban Verbs: Hip-Hop Conservatory & Theater and is the founding president of Beyond Poetry LLC. His first book, SWEAR (West End Press/UNM Press) won the Tillie Olsen Award for Creative Writing from the Working Class Studies Association. Bellmay was awarded the Emerging Creative Bravos Award by Creative Albuquerque in 2013. In 2014, Bellamy was named a W. K. Kellogg Foundation Fellow and was awarded the Food Justice Residency at Santa Fe Art Institute. In 2017, Bellamy was selected as Kennedy Center Citizen Artist Fellow. He received the University of New Mexico Paul Bartlett Ré Peace Prize Career Achievement Award in 2018. He is also the featured artist and moderator for Creative Santa Fe’s upcoming Disruptive Futures Dialogue: The Rebirth of Local News, highlighting the work of journalists and news organizations who are engaging with local audiences to create trust and provide news that people can use to effect change in their communities. It is an honor to ask Hakim Bellamy three questions: QUESTION 1: In a recent ArtPlace article the author said that “perhaps one of the greatest gifts that the arts bring to municipal planning is not a set of discrete answers, but rather a call for planners to rethink some of our fundamental questions.” Your work frequently exists at the intersection of poetry and policy, likely now so more than ever in your role as Director of Cultural Services for the city of Albuquerque. In your opinion, how are the arts critical to civic policy and municipal planning? The obvious direction to go with here stems from La bohème and its derivative work Rent. Artists often live, love and libretto amongst the most brutal social and economic realities … whether it be Paris in the 1840s or New York’s East Village in the late 1980s. Though artists themselves often have privilege, whether inherited or born of their talent, their circumstance often finds them in conversation with the human condition, oftentimes at its most critical. Sometimes the allure of the artist is the sheer power of their observation and ultimate expression, other times it is the ferocity of their compassion that leaves them emotionally raw. Both transferrable skills in government genuinely concerned about the wellbeing of the constituents in its care. The latter skill is especially important with respect to holding space for the needs of those in the community who have never been invited to be decision makers at the tables of power. The less obvious, and much shorter answer is that all solutions are creative. The government’s job is to find solutions to our most persistent issues. If what we were doing worked, our problems wouldn’t persist. Therefore, creativity is required to both imagine different outcome and engineer a different process to achieve it. Artists do it all the time…they create employment opportunities for themselves out of thin air…however in order to scale it for broad economic impact, you make sure you have friends that are smarter than you over in the Economic Development Department. I should mention that poetry, in particular, is often a philosophical wrestling with the issues of identity and society. Who are we? What should we be doing for one another, rather than to one another? Those are questions I hope our leaders would frequently ask themselves and each other, and not only when they are trying to get published. QUESTION 2: You have been a professional artist in New Mexico for over ten years. What are some of the opportunities and challenges you have faced carving out a career as an artist, author, and educator over the years? What advice would you give to aspiring artists throughout New Mexico? The opportunities have far outweighed the challenges. I landed up, as we say, in New Mexico in 2005 from the South Jersey/Philadelphia area. I suppose since I came from the northeast you could say I landed down? Actually, I imagine we simply call that “landing.” Or perhaps, since we are proximal to Roswell we should call it an arrival. Whatever it was, it was on MLK Day in 2005. An auspicious date for a Black man from the East Coast to set foot in a New Mexico he’s never seen before. A state with, at the time, 2% African American population…on what I like to call “the holiday honoring the patron saint of Black America.” Coincidence is not lost on me, neither is it found. Two months later I was the University of New Mexico LOBOSLAM Champion. Two months after that, I was the Albuquerque City Slam Poetry Champion. Four months after that, we were National Poetry Slam Champions as Team Albuquerque. I was fortunate to step into a performance poetry community that had built ten years of foundation. Audience building. Talent development. I was additionally fortunate that this City took me and the things I care about, the things written all over my poems, to heart. I still marvel at being selected the Inaugural Poet Laureate of this exceptional place … because I write about my experience, the Black experience in America … and apparently, it resonates. People see me. People hear me. People read me. People remember me. People keep coming back for more. Albuquerque has literally allowed me to stand on its back (read: mountain) so other parts of the country could notice my talent. Provided me a platform, and in return…I’ve strived to tell the story of the place, even though I am not originally from this place. But without this place, there is no Hakim Bellamy. No career. No son. My son was born here. It truly is a blessing. However, there were some obstacles. Like being a working parent when your work requires traveling out of state to make ends meet. In the early part of my career, where I was equal parts paying dues and paying rent while doing what I feel I was born to do…inspire others to create…there weren’t quite enough $50, $100 gigs for me to cobble together to not be living check to check. I always kept a second “job”…a job secondary to my career…that provided a little financial stability for myself and my son. I made time to create within those limitations. Did a lot of writing in airports because although Albuquerque gave me all the gigs I could afford…the larger pay days for performance artists where at colleges and on stages in places with more disposable income. I love traveling, so seeing the world was a blessing, but frankly, it made it difficult to maintain healthy relationships with romantic partners, including my son’s mother at the time. I could have said “no” more. That would be my advice, be intentional with your time and talent. I can’t say it served me poorly, but I have no idea how much good it would have served me…in sanity, in healthy, in quality of work versus quantity of work, in friendships. However, I am like many artists (and marginalized people) in that we suffer from this imposter syndrome. This feeling that we don’t deserve all the opportunities that we are being given, so we can’t waste even one … because we don’t know if there will be another offer on the other side. Because we’ve been sold on this idea that we are not good enough, so we work twice as hard for the same opportunities that our peers gain through training or superhuman powers … like where, how or what they were born. It’s not rational, but it is real. If I was more confident in my talent, and trusted the arch of my career to the universe I might have stepped back occasionally to leap light years forward. I’d tell all my young writers, “give yourself a residency from time to time. Make self-care, not selfish, your career.” QUESTION 3: You were recently a 2017–2018 Kennedy Center Citizen Artist Fellow. The fellowship examines the crucial role that arts and culture play in shaping society. This fellowship is described on the Kennedy Center website as “Activating Citizen Artists. Exploring JFK Ideals. Creating Cultural Moonshots.” Among your collaborators was legendary cellist, humanitarian, and Kennedy Center Artistic Advisor at Large Yo-Yo Ma. Can you talk a bit about this remarkable fellowship and your work with Yo-Yo Ma? Yo-Yo Ma’s passionate desire to transform the world through the sharing of art is as formidable as his prodigious talent. He lights up a room and everyone in it. He believes he is extremely blessed to live a certain caliber of life and have certain experiences because of his art, and he demonstrates that humility by being exceptionally present when he is with you…all the way down to remembering your name. That was some of what the Kennedy Center experience taught me. To stay graceful and grateful. That giving people my undivided attention is more medicine than authoring their favorite poem…especially if they are a lover of my poetry. By and large, that group of Citizen Artists (who I have to name so you look them up: Ekene Ijeoma, De Nichols, Reena Esmail, Michelle Angela Ortiz, Katie Wyatt and Vijay Gupta) shaped me with their fire and their friendship. Their ability to see a need in their community and fill it with opportunity for others. We compared notes, we collaborated on art, we discussed the future of the fellowship and we committed ourselves to the Aspen Institute’s definition of Citizen Artists as: Individuals who reimagine the traditional notions of art-making, and who contribute to society either through the transformative power of their artistic abilities, or through proactive social engagement with the arts in realms including education, community building, diplomacy and healthcare. Bonus Question: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? Alexandra Bell’s “Counternarratives” work comes to mind, especially on the eve-eve of Rebirth of Local News. I first met Rachel Bronson two years ago when I joined a small team in Chicago to help launch the Arts Science Initiative for The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. For over 70 years, The Bulletin has been bringing together science leaders, policy makers, and the public to address global existential threats. The goal of the Art Science Initiative is to create a powerful platform where artists can present their work, interact with scientists, develop new ideas at the intersection of art and science, and engage new audiences committed to solving the globe’s most urgent issues.

In her role as President and CEO of the Bulletin, Rachel oversees publishing, the Doomsday Clock, and activities around nuclear risk, climate change and disruptive technologies. She was previously on the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, an adjunct professor at the Kellogg School of Management, and served as senior fellow and director of Middle East studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. Her book, Thicker than Oil: America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia (Oxford University Press, 2006), has been translated into Japanese and was published in paperback in June 2008. Her writings have appeared in publications including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The National Interest, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Huffington Post and The Chicago Tribune. She has appeared as a commentator on numerous radio and television outlets, including National Public Radio, CNN, al Jazerra, the Yomiuri Shimbun, “PBS NewsHour,” “The Charlie Rose Show,” and “The Daily Show.” Rachel has served as a consultant to NBC News and testified before the congressional Task Force on Anti-Terrorism and Proliferation Financing, Congress’s Joint Economic Committee, and the 9/11 Commission. Bronson was named by Today’s Chicago Woman magazine as one of 100 Women to Watch (2012), 20 Women to Watch by Crain’s Chicago Business (2008), a Carnegie Corporation Scholar (2003) and a Glamour Magazine “Wow Woman” (2002). We recently reconnected in Santa Fe to continue our work on the Arts Science initiative with a team of talented artists, makers, and creative thinkers from Santa Fe. Here are three questions for Rachel Bronson. QUESTION 1: One of the most recognizable aspects of The Bulletin is The Doomsday Clock an iconic image created in 1947 to visually depict the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe by nuclear war and climate change. Midnight is global catastrophe, we are currently at 2 minutes to midnight. The Bulletin garners the attention of scientists, politicians, diplomats, and organizations such as the United Nations. The Clock has also recently captured the attention of popular culture—including such iconic political satirists and popular news shows as Steven Colbert, Whoopi Goldberg, and TMZ. As a result, some of the most intractable and vexing issues of our time are accessible to much wider audiences globally. What is it about The Doomsday Clock that makes it so accessible, and why do you think it has the ability to capture the attention of audiences far beyond experts in the field? The magic of the clock is that it is blunt and deceptively simple. It boils down a tremendous amount of expert information about existential threats into one basic number, the time on the Doomsday Clock. The creator of the Clock, Martyl Langsdorf was married to a Manhattan Project physicist, and she spent time with the leading scientists and civic activists of her time. She understood at a gut level that her scientist husband and his scientist friends were desperately concerned about science and technology’s advancement, and its ability, for the first time ever, to alter the future of humanity. These scientists were looking for ways to engage the public about the revolutionary changes that were underway, and get their help in demanding responsible global policies to keep us safe. Martyl poured all of this into her image. Those scientists also understood that they alone couldn’t mobilize the public and convey the urgency they felt. They could publish the best and smartest articles, but if no one read them, it wouldn’t matter. They were smart enough to understand art’s power, and to reach out to Martyl to design a cover to their magazine. And boy did she deliver. Her clock conveyed the sense of urgency and agency that they were looking for. Readers suddenly understood that they could turn back the hands of the Doomsday Clock, but they had to act quickly. In 1949, in response to the Soviets testing their first atomic weapon, the editor of the Bulletin, Eugene Rabinowitch, moved the hands of the Clock forward from 7 to 3 minutes to midnight, making Martyl’s static design dynamic. 71 years after it first appeared, the Doomsday Clock has moved 23 times, and has captured the public imagination. In its blunt simplicity, it allows everyone and anyone to join a conversation about whether or not we are today safer or at greater risk than we have been across the past seventy plus years we have been moving the clock. Today, the clock time includes not only nuclear risk, but climate change and other disruptive technologies. That is because our board believes that you can’t answer questions about the future of humanity without considering such issues. Technology has evolved since 1947, when nuclear risks were the only existential threat. We have a lot more information about the Clock on our website at https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/ QUESTION 2: As I mentioned in the introduction, the Bulletin has been building an Arts Science initiative over the past few years. We now understand that the arts are a critical point of access to much wider audiences, to broaden channels of communication, and to drive change through the power of numbers. What have been some of the biggest challenges you have faced in integrating the arts into your work at the Bulletin? The Bulletin has been able to attract science and policy experts from around the world who work on existential threats. It is possible to attract such expertise because we’ve been working on this issue for over 70 years. Back in the day, we would receive submissions from artists from around the world as well to appear on our cover as well as in our pages. We lost many of these connections and our internal expertise when we went digital in 2009. With our new Arts Science Initiative, we intend to reintroduce the arts into our offerings because in this highly digital world visual imagery has the power to engage and mobilize, and the future of our planet demands nothing less. However, we also have to be very careful that whatever art we publish is as technically sophisticated as our existing contributions. Therefore, we are building out our network to connect with recognized arts leaders to help us identify leading talent that is working responsibly on our key issues of nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technology. We want to connect them with our scientists to also ensure that their art is scientifically grounded. Building the arts expertise to match our existing scientific expertise is not straightforward, but I am confident that we will get there. The arts expertise exists, we just need to find it and connect with it. QUESTION 3: When artist Martyl Langsdorf created the Doomsday Clock, one of the most compelling and critical aspects of this project was the connection between the arts and sciences. We have spoken at length about this connection, and how the arts can be engaged to disseminate these issues to much broader audiences. Why do you believe that now, more than ever, art is critical point of access to disseminate messages, build audiences, and ultimately tip the power balance to drive change? We know that images and stories captivate broad audiences, and can amplify the work of leading experts. We all know that the movie Dr. Strangelove helped generations of viewers experience at a gut level the dangers and absurdity of the nuclear arms race. What many might not know is that Stanley Kubrick got his idea for Dr. Strangelove from an article he read in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The power of the film is that it’s a great film, but also that it rests on significant technical expertise, and a pretty deep understanding of nuclear strategy. Powerful art is not created in a vacuum. It often draws on a tremendous amount of technical knowledge, in addition to a keen sense of the political issues of our day. This is why we are delighted by the Take Back the Clock exhibit now on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We worked closely with them in developing it, to provide a hands on experience for a new generation to engage on issues of nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies. Also we worked closely with new media artist Ellen Sandor to create a virtual reality tour of the Doomsday Clock using Martyl’s color palette and iconography. Today, I believe we are in serious need of new images and expressions not only around nuclear risk, but climate change and particularly disruptive technologies. There are huge ethical questions facing us right now around gene editing, artificial intelligence, and cyber to list just a few. We know, that science’s advancement will bring huge benefits. It will raise millions out of poverty, advance health care and quality of life, and extend lifespans. But we also know it brings great risks. It will threaten the employment of millions, has the potential to create designer babies and undermine democracies. I firmly believe that science is neither good nor bad, but both. It’s the public policies that we bound it with that will tip the balance about whether it’s on balance helpful or harmful. BONUS QUESTION: Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? I find the work of Jennifer Doudna quite fascinating as I do the Partnership for Artificial Intelligence cofounded by Bulletin Board of Sponsors member Eric Horvitz. Jennifer is a leading developer of the gene editing technology CRISPR. Her scientific breakthroughs are leading to enormous advancements in healthcare, and someday may help us cure cancer and genetically-caused diseases. However, Dr. Doudna is also quite concerned about the ethical questions that has surrounded her gene-editing tool. She and some of her colleagues have called for a worldwide moratorium on the use of CRISPR until scientists, ethicists and the public fully understand the issues surrounding its breakthrough. I am in awe of her position. She is clearly a huge advocate. She invented the technology. But she also understands better than most what is at stake. This kind of ethical struggle is exactly what the Manhattan project scientists experienced, and is why they got as engaged in politics as they did. I find Jennifer Doudna’s concerns a direct extension of the kinds of issues the Bulletin has been doing for more than 70 years. I also find fascinating the Partnership for Artificial Intelligence (AI). The partnership is made up of leading pioneers in the field of AI. Like Doudna, they also recognize that artificial intelligence has the potential to bring benefits but risks as well. Participants are trying to better understands the risks of AI so that we can build better policies that will allow us to avoid its risks, while leveraging all the benefits it will bring. There are important similarities between what Doudna and Horvitz are doing, even though their fields of synthetic biology and artificial intelligence are quite different. Both are advocates for science’s advancements. Both realize that the public needs to get engaged to advocate for good public policy. At the Bulletin, we hope that our arts science initiative will provide new ways to understand all the benefits and the risks, to engage the public to advocate for a safer future. Photo by Amy Pinard A couple of years ago I was at my neighborhood nail salon, The Today Show was playing in the background. I was distractedly watching when I noticed a poised, articulate, and wildly stylish version of my childhood friend Hitha Prabhakar discussing Black Friday shopping with Carson Daly. The last time I saw Hitha was probably on an elementary school playground in Albuquerque, New Mexico, but this had to be her. A quick google search confirmed that this glamorous powerhouse was the Hitha I once knew. She is now enormously accomplished, living in New York, and married to comedian Seth Herzog.

Hitha is the Chief Research Officer at H Squared Research LLC, a research firm for investment advisors and is also the Executive Producer and Co-host of the podcast “Divided States of Women”. She has been featured in Vogue India, New York Times, Shape magazine, Glamour magazine, Marie Claire, Oprah magazine, Lucky magazine, The Daily Mail, Style.com, Forbes.com, Huffington Post. She was recently named by Forbes as “one of the most influential South Asian women in the United States. Her television appearances include NBC Nightly News, The Today Show, Fox Business, MSNBC, Bloomberg TV and CNBC. She has written for Time magazine, MSNBC.com, nymag.com, Today.com, People magazine, People.com, and ELLE India. She advises start-ups in Silicon Valley, Parsons The New School of Fashion incubator XRC Labs, and teaches a class on social commerce. Hitha is also dedicated to raising awareness about criminal activity linked to the black market and counterfeit products. She is the author of Black Market Billions: How Organized Retail Crime Funds Terrorists and created an app to help people identify and spot counterfeit merchandise sold on the black market. What an honor to reconnect with this remarkable woman. QUESTION 1: Your career is strikingly wide-ranging. You are an investigative journalist, teacher, retail analyst, fashion icon, and the wife of a famous comedian. On your website you describe that you live in a world “where fashion, retail, finance, investigative journalism and data research all co-exist in perfect harmony.” How do you balance these disparate interests and roles, and why is it important to you to lead a life of such contrasts? When I was in graduate school, a professor told me as a journalist, it wasn’t enough to compartmentalize your skills. Meaning- in order to be successful we had to know how to write and edit, shoot video, record on radio, be in front of the camera, etc. His words really stuck with me. I developed an expertise in a specific beat (retail) and was fortunate to be able to liaise it into so many different mediums that all work together. On paper it looks like a big contrast, but in real life it’s more like being a conductor of an orchestra. QUESTION 2: Your book Black Market Billions is an in-depth investigation of retail crime rings and how counterfeit goods fund organized crime. How did you become so engaged in this issue, and what was it like to dive so deeply into this world—going so far as to risk personal harm to interview some of the criminals themselves? I had randomly received an email from a former colleague at a magazine I was working for asking if I wanted to buy a very inexpensive but very “real” Givenchy handbag. We were talking $400 for a $2500 piece. Wary of how sketchy this all was, I asked him why the bag was so inexpensive. He told me it was stolen via an organized retail crime ring at a major luxury store. My investigative senses went off like a blaring alarm. I decided to follow the story, which lead me to the creepy world of black market of counterfeit and stolen goods. My editor at Financial Times Press loved the idea of this becoming a book, so she gave me nine months to write it. Doing the interviews was terrifying at times. At one point, I was following the trail of stolen and counterfeit car parts going from Albuquerque to Palomas, Mexico. The Albuquerque Police Department told me which criminals were involved and what I should be looking for. But for obvious reasons (me being by myself in my mother’s car were a couple) had some reservations about going. Seth [Herzog] was the one who convinced me to go by saying “What would Bob Woodruff do?” So I went. I was terrified but the experience brought the entire book together. As of today the counterfeit industry is a $460 billion industry, and the more we shop online the more we are susceptible to purchasing fake, potentially harmful merchandise. It is so important people know this as they shop, click, swipe away on their phones, computers and tablets. As of today the counterfeit industry is a $460 billion industry, and the more we shop online the more we are susceptible to purchasing fake, potentially harmful merchandise. It is so important people know this as they shop, click, swipe away on their phones, computers and tablets. If I can help raise awareness in any way, I’ll do it! QUESTION 3: You have clearly led an extraordinary life and are enjoying a tremendously successful career. What have you not yet done that you have always wanted to do? What is next for Hitha Herzog? Ha! It doesn’t seem extraordinary at all! I am so lucky to do what I love. Each day is different and I can’t imagine it any other way! I would love to write a novel or a script for a movie maybe based on the novel I would potentially write. Fiction is such a different beast than non-fiction. You have to use an entirely different more creative part of your brain. I have this ongoing fantasy in my mind where I take off one day, set up in Marfa, TX, do retail research for half the day and write for the rest. Fiction is such a different beast than non-fiction. You have to use an entirely different more creative part of your brain. I have this ongoing fantasy in my mind where I take off one day, set up in Marfa, TX, do retail research for half the day and write for the rest. Not sure what the comedy scene is like in Marfa, so Seth and I will probably be in NYC for the foreseeable future! One More Thing... Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? Wow. There are so many people I could name here. I think the obvious choice is Elon Musk, but Bjarke Ingels is a genius and has completely changed the NYC skyline in the most amazing way. In fashion design, Alessandro Michele completely changed Gucci’s profitability by making street wear aspirational and there are the genius co-founders of ADAY, Meg He and Nina Faulhaber. These women have completely changed the landscape for activewear/workwear crossover apparel that looks fabulous. I had the great pleasure of meeting Colombian American Artist Yazmany Arboleda at the Abu Dhabi Culture Summit last April. Like his work, Yazmany radiates optimism, élan, and wonder in a world that increasingly seems bleak, fractured, and hostile. He has been engaged in the practice of creating what he calls “Living Sculptures” for over a decade, bringing people together to transform their experience of the world, and in doing so strengthening communities across the globe. Yazmany brings beauty, humanity, new paths of engagement, and a sense of meaning and belonging to cities ranging from Kabul to Johannesburg, Nairobi to New York. Yazmany is the Co-founder and Chief Creative Officer of the creative agency limeSHIFT. He is also Creative Director of the Brooklyn Cottage, Associate Director of Communications for Artists Striving To End Poverty, and a co-founder of the interdisciplinary performance collective Shook Ones. He lectures at UNC, MIT, and other institutions internationally about the power of art in public space. His work has been written about in the New York Times, Washington Post, UK’s Guardian, and Fast Company. In 2013, he was named one of Good Magazine’s 100 People Making Our World Better. Question One: You are a trained architect, artist, writer (and might I add distractingly good dancer – still jealous of the spontaneous backflip on an Abu Dhabi dancefloor). You have so many extraordinary skills and talents to offer the world, how did you decide to make social practice art your primary career focus? In 2007, I was privileged to have my first solo exhibition in New York City. The name of the exhibition was ‘The New Vitruvians’, and it was made up of large scale portraits. The people, from all different walks of life, were photographed and made to look like they were made of plastic. The photos were then printed three dimensionally onto 50,000 neon bouncy balls. For six months my family, friends, and co-workers came to my home and office (I was working as a creative lead at a communications and branding agency named Imagination at the time) to push bouncy balls into plexiglass sheets. The night of the gallery opening, I realized that many of the guests who were there to celebrate and experience the work had been robbed of all the late night conversations about skin colors, privilege and beauty that we had all had during the making of the pieces. They had missed out on the journey of getting to know strangers–people like yourself, who thought that going to help out an artist by pushing hundreds of bouncy balls into holes in downtown Manhattan would be a cool thing to do. From that point forward, I began investigating how people engaging with art IS art. I begin thinking and experimenting with ideas about how the art that hangs on our walls and occupies our space could be more meaningfully transformative. I came to this: to have been a part of the making of the thing, to have told stories while there … THAT is important. It’s a visual manifestation that we are here, we exist and we are interested in finding beauty, together. Question Two: In the introduction to the essay “How Colour Replaces Fear” in the recently published book Art and the City: Worlding the Discussion through a Critical Artscapeyou describe how each of your projects aims “to provide the community with new tools to engage in dialogue, rekindle ownership of their environment and generate interactions that inspired love, inclusion, and belonging.” Clearly this is needed in our world now more than ever. Can you speak a bit about the importance of social practice art, what it means to you, and perhaps how that has changed over the years you have been involved in this type of social engagement? What social practice art does, in my opinion, is that it transforms ‘art’ from an abstract noun into an inclusive verb. It turns the object-based narrative of art into a dynamic collective story that is also personal. The academic Doris Sommer, who is the director of the Cultural Agents program at Harvard, believes that art is ‘that which has no name yet’. When I began building projects with communities, I attributed many of our choices to experimentation. We were creating, then studying responses, rapid prototyping, and creating again – beginning the whole cycle anew. When I came up with Monday Morning, the project where local artists and activists give away 10,000 biodegradable balloons to adults on Monday Morning to honor them as they go back to work, I was interested in exploring how different cultures around the world would react to this gesture. In Bangalore the balloons were orange, in Yamaguchi they were green, and in Nairobi they were yellow. By the time we did the project in Kabul, Afghanistan, we had learned so much from our previous successes and failures that we were able to begin to formalize our process. With time, we learned that one of the critical pieces of creating meaningful social practice art is to have as many of the stakeholders involved from the beginning as possible: governmental leadership, possible sponsors (private businesses that would benefit from the network being built and the visibility of the project when executed), NGOs, and relevant civil society organizations. If you want people to have a feeling of belonging, then they must be present from the inception of the idea all the way through to the crafting and eventual execution of the art intervention. Working together, the team defines the scope of the work, the schedules, financial requirements, and project milestones. Being a part of the decision making process is critical to connecting with each other meaningfully. When I began exploring the field of social practice art, I was creating experiments for myself. Organically, the work invited me to bring others into that experimentation and allow them to question, push, and pull the work, shaping it beyond my control. Learning to let go of that control and give it to all the people who bring this work to life continues to be my greatest lesson in life. Question Three: Your current project is Espejismo is a large-scale community installation of mirrors, asking people from all walks of life to lend their mirrors and their stories with the underlying assumption that by seeing how others see and by letting them see how we see, we can collectively move the world forward in a considered way. Each Espejismo project becomes a monument to, a reflection of, the community where it is created. It was first shown at Yale University and is now traveling to Carnegie Hall where it will be on exhibition there for a year. Can you tell me a bit more about this project, how you envision it traveling to other communities in the futures… perhaps to Santa Fe? While we were at the Abu Dhabi Culture Summit, I had the privilege of meeting the inspiring president and chief executive officer of Vital Voices Global Partnership for women, Alyse Nelson. I shared with Alyse that we were looking to borrow reflections in New Haven: we wanted to hear about how people wanted to be seen by others, collect their stories, and literally ask them if we could borrow a mirror from them. We would lay all those reflections down next to one another, and we would tell each other stories. The original thought was that we would borrow each others reflections in hopes of helping the world see itself. Alyse connected me to Dr. Deqo Mohamed who was living in New Haven as part of the Yale Global Fellowship Program. When I met Dr. Mohamed for tea one afternoon she greeted me with a smile and a compact mirror. She shared that she spent a meaningful part of her life as a refugee in Russia and the United States. When I asked about what shaped her early on, she told me that when she was fifteen years old she was helping her mother deliver babies while a brutal war was engulfing her home town and much of Somalia. “When people see you, what would you like them to know?” I asked. “I want them to include me in their definition of the word refugee. I want them to see me as a survivor of war and thriving physician. As a refugee, I pursued a medical education, came back to Mogadishu and helped build a hospital. That hospital is now a village.” Today, she leads all operations in the Hawa Abdi Village in Lower Shabelle, while ensuring the safety of the 300 families who have found permanent shelter in the community. This includes a 400 bed hospital and a school for all the children growing up there. There are so many beautiful tales. Dr. Mohamed connected me with a safe-house for East African refugees in Connecticut. They too shared their stories and let us borrow their mirrors. Among the final tapestry of the installation were the mirrors of 14 undocumented immigrants and two Pulitzer Prize-winning authors. The wide variety of humans that came together to create this first version of Espejismo was humbling. So the hope is that this idea gets picked up by people who want to see each other: better, differently. One more Thing… Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? The scale of this question led me, at first, to think globally. I considered Buddhist nun Pema Chodron and author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I thought of countless miracle-working leaders across industries and continents. I thought of London-based aeronautical engineer Ryan Yasin who invented clothes that grow as children grow. Now THERE is a man who knows how to wear his artist hat. I wonder if people ever told him to ‘be realistic’? Then, I thought locally, about the people who own acres of my own heart because they showed up to make things with me in the name of art. I finally settled on Consuella Lopez, a transgender hair stylist, community organizer and activist living in Washington, D.C. Consuella volunteered to be the hair stylist for a fashion show that I was orchestrating for my Master’s of Architecture thesis presentation at Catholic University. There would be a film, a play, a fashion show with all the clothes tailored from architectural materials, all about a building commissioned to house the Museum of Fashion and Textiles in New York City. I tell myself that less is more all the time and… after many years I have learned to make the gestures more nuanced and simple. But at the time I wanted… Pompadours like Tom Ford’s advertising campaign for Yves Saint Laurent’s Fall 2002 collection! Consuella Lopez showed up and showed us what a proud transgender woman looks like and feels like. She was professional, kind and incredibly talented – and the pompadours were fantastic. Today, Consuella is the chief operating officer of Casa Ruby, a haven for the transgender community in D.C. She is now serving her third term as a Political Appointee for the D.C. Mayor’s Office of LGBTQ Affairs. She didn’t have any transgender role models when she was growing up, so when the opportunity came, she readily agreed to be the face of a campaign championing trans-rights. Her smile is on buses, train stations, and billboards next to the words “I am a transgender woman and I am a part of D.C.” As the master stylist for NBC Universal in D.C., she styles media personalities like Anna Wintour, Rachel Roy, Kellyann Conway and Paul Ryan, happily posing with them for Instagram. She shows up as her most generous self, regardless of that day’s TV guest, and shows them what a proud transgender woman looks like and feels like. She is a living example of what it means to live with curiosity, compassion, and courage. I suspect what drives Consuella to do the work that she does mirrors what drives many of us: she lives day to day looking for more people to love who are brave enough to love her back. Smriti Keshari is an Indian-American award-winning filmmaker, artist, and director. Her work explores untold stories beyond mainstream media. Her approach is interdisciplinary and deeply collaborative, bringing together artists, actors, musicians, scientists, writers, activists, and other creative minds to push beyond traditional constraints of film making.

I first met Smriti in Los Angeles to preview her extraordinary collaborative film/music/art installation the bomb. the bomb is an immersive multimedia experience that the New York Observer describes as “an abstract wonder and a literal nightmare: a dazzling view into the abyss.” The 61-minute video installation places the viewer in the center of archival footage, animation, music, text, and live music performed by the band The Acid. the bomb debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in October, 2017, has since premiered internationally at the Berlin Film Festival, and was featured at the 2017 Glastonbury Festival. It’s available to be viewed on Netflix. In 2018, it is embarking on a global tour starting in Sydney. Here are three questions for Smriti Keshari. Question One: Originally from India, you grew up in Puerto Rico, traveled throughout Australia, produced a surfing series in India, produced the extraordinary documentary Food Chains examining social injustices impacting American farmworkers, and now ‘the bomb’. Your interests, travels, and experiences are sweeping; your projects seemingly disparate. Can you speak to what most inspires you, why you are drawn to travel and adventure, and how that informs the stories you tell? I recently spent some time in Liverpool, and was telling a friend about how I typically need to be in an airplane and on the road to obtain clarity. On the road comes naturally to me. When we’re on the road or in nature, there’s a lot of waiting and pondering, you just sit there, what we’re really doing is just switching off various kinds of alertness that we don’t have to use. We stop being active, or even, defensive. We just welcome different types of experiences, and in that there are hidden things you’re drawn to discover. Question Two: My experience of ‘the bomb’ at the Tribeca Film Festival was vertiginous, uncomfortable, and deeply moving. The room was crowded with people and the range of reactions was vast—tears, embraces, awe, stunned silence—someone near me was physically ill. The bomb provoked a far more profound response than a lecture or a public service announcement could ever conceivably elicit. Why was it important for the viewer to be in the center of this experience, rather than just a passive viewer? Why do you think the arts are an important vehicle to address urgent, global issues? For some time, I had been thinking about putting people inside of a film, challenging the one-way, one-directional experience of viewing. Whether it’s a film, a theater performance or a live music show — these are always projected at you. But what if you were in the center of the story? How would your perception of it be different, by changing the way you experience it? Around this time I was reading Command and Control, and it had a profound effect on me. It became evident to me that we’re living under this most awful nuclear cloud, in a world with roughly 15,000 nuclear weapons. Yet, there’s a complete ignorance of them. These weapons are buried underground, they are out of sight and out of consciousness. The idea of nuclear war is abstract and unfathomable. The human imagination is incapable of encompassing all the psychological variants of this reality. And it’s really hard for an individual to have an emotional connection to something that they can’t see, or feel. I really wanted to create a deeper, visceral experience of nuclear weapons, so people could feel the gravity and reality of living with these weapons. There’s an entire system, processes, timing, reasoning that led us to this reality. In order to understand how we’ve gotten to this reality, we must first recognize the emotions nuclear weapons evoke — their allure, their beauty, their construct, and the ultimate death wish at the heart of them. the bomb was made to deliberately ignite an emotional and visceral understanding of the nuclear reality we are living in right now. Eric and I brought together the experimental spirit of Kevin Ford, the bold and political art of Stanley Donwood, the technological and visceral viewing ethos of United Visual Artists (UVA), and fused it all together with the haunting live soundtrack by The Acid. Question Three: Having The Acid perform live during the installation unquestionably increased the immediacy and intensity of my experience as a viewer. My entire body vibrated to haunting and powerful instruments and vocals in real-time response to the images that engulfed me. How did you come to work with The Acid? Can you speak a bit more about your choice to use such an interdisciplinary, collaborative creative approach for this project? Adam Freeland and I had met many moons ago through a mutual friend, who had suggested I check out The Acid’s album Liminal when Eric and I were discussing the different sounds for the bomb. Through a powerful underlying simplicity, The Acid propel the listener into an emotional journey. In early creative conversations with Adam while hiking in Griffith Park, he often spoke of the art of a good DJ set in terms of building and releasing tension and then building again. The Acid are adept at creating space, magnitude and depth by holding back where others might want to go bigger. Silence was certainly a favorite topic of mine that we discussed. Silence can sometimes be viewed as the antithesis of sound, but silence needs to exist for one to experience sound. It consist of it, you need one to experience the other. Kind of like dark matter in the universe. So, we would often debate what silence sounds like. As a filmmaker, before thinking of any scene I often think first of the music and sounds that would help convey the emotion. In the process of making the film and the original score, we often spoke about how nuclear weapons tapped into different emotions – of adrenaline, of fear, of celebration, of chaos, of sadness, etc… — and how the music can heighten those feelings. In a sense, each aspect of the film inspired the others. There’s a moment during the bomb, where we focus on the seduction of the machine — each entity of the experience, from the film to the animation to the music and the multi-screen configuration, follows a slow seduction, than a build and a climax — ending in almost a euphoric hallucination with the nuclear weapon at the center of it. One more Thing… Who do you think is doing the most innovative, interesting, disruptive work right now and why? I recently saw Trevor Paglen’s exhibition A Study on Invisible Images on the vision of machines. Trevor’s piece focuses on visual culture and process of machines — how an algorithm or an AI “sees”. I’m creating a new project on artificial intelligence, and the subject matter is quite complex because at the heart of A.I., you’re defining intelligence — which is in itself, an endless pursuit. Trevor’s approach is quite simple, yet revelatory. Also, I’ve been listening to Nordic Affect, an Icelandic group that combines classical and new music — violin, viola, cello and electronics — and has a rhythmical repetition. It sounds like you’ve stepped inside a giant clock, it’s calming yet quite gothic. Houston-based artist Dario Robleto was recently described by Krista Tippett of onbeing.org as “famous for spinning and shaping unconventional materials — from dinosaur fossils to pulverized vintage records, from swamp root to cramp bark. He joins words and objects in a way that distills meaning at once social, poetic, and scientific.” His art projects bleed fact and fiction, science and art, truth and myth. Dario’s work, interests, and medium span far beyond the traditional boundaries of art and art-making, as evidenced by his recent participation as a panelist for complexity science research center Santa Fe Institute’s InterPlanetary Project in partnership with Creative Santa Fe. Science fiction authors, scientists, filmmakers, and artists came together for this event to discuss the political, scientific, environmental, and ethical ramifications of what it means to become an InterPlanetary civilization. As a panelist, Dario discussed his position as Artist in Residence at the SETI Institute, an organization dedicated to searching for extraterrestrial life. He also recently served as the artistic consultant to Breakthrough Message, a multi-national effort that aims to encourage intellectual and technical debate about how and what to communicate if the current search for intelligent beings beyond Earth is successful. I wanted to learn more about Dario’s role at SETI; his perspective on how the arts can shape (or reshape) our worldview; and, of course, his thoughts on the ramifications for our civilization if we ever do make contact. Question One: As an artist-in-residence at the SETI Institute and as artistic consultant to the Breakthrough Message team, you have spent much time contemplating the problem of universal message design as it relates to possible contact with other intelligent life in the Universe. Why do you feel it is important that artists be represented on these teams? Historically, the problems SETI and Breakthrough pursue have been problems of the natural sciences and mathematics that engage astronomers, astrophysicists, astrobiologists, encoding and transmission experts, and more. But because of the complex nature of the problem, the field must embrace a wider knowledge base if it is to move forward. More recently, we have seen the social sciences, through disciplines such as linguistics, anthropology, archeology, psychology and sociology, contribute meaningful dialogue to the field. But for various reasons, the arts have lagged behind when being invited into this discussion. This has always struck me as odd because art’s ability to create aesthetic experience—the vehicle for communicating complex intellectual/emotional states of one’s existence—is crucial to understanding one of the most profound questions we can ask: are we alone? To ponder the nature of aloneness and the deep need to satiate the longing it inspires—either at the level of an individual human life, or at the planetary scale of an entire species unsure if it will ever know companionship across the cosmos—is a problem the arts have much knowledge to contribute to. Science and engineering may enable us to figure out how to detect or send an interstellar message; the arts enable us to ponder why we are asking if we are alone in the first place. While I firmly believe the arts can enrich, even lead the way, on some very practical levels of interstellar message design and detection—how one encodes altruism in various forms, for example—there is important work to be done in communicating to our own species why it continues to be crucial we think of ourselves within a larger cosmological scope. The palpable sense of fresh energy from Breakthrough, and NASA and SETI’s innovation in detection approaches, make it clear to me we are likely on the threshold of finally answering if there is life elsewhere in the Universe. In fact, in 2015 at a congressional panel, the chief scientist at NASA made an announcement, which included a timeline (a few decades) to the discovery of the existence of life beyond our planet. This public statement of timelines on such a sensitive topic by someone of her rank is generally unheard of in her field. It should absolutely be stressed though that she was referring to the detection of microbial life, not the detection of “intelligent” signals of a technologically advanced civilization. Regardless of the type of life we may find, someone born today is likely of the first generation that might live with the knowledge that we are not alone. It would be unacceptable for the arts to not be actively involved with arguably the most profound existential revelation of our time. Question Two: What are some of the challenges of designing a message to send to a hypothetical alien world that we know absolutely nothing about? What insights may we gain about ourselves in the process? On a more conceptual level, the problem of interstellar message detection and design is one of the most interesting thought experiments I have encountered. The problem, as you mention, is how does one communicate with something that they can’t imagine? This is an extremely difficult conundrum when our only examples of intelligent life are of ourselves and other species on Earth. It is extraordinarily unlikely another intelligence on a remote world would have evolved in the same way and thus would present an intelligence different than that on Earth. Besides the particular environmental conditions of each world, which would affect different evolutionary paths, we also cannot assume life elsewhere is even a water or carbon based form that uses DNA as its means of carrying genetic information. How these variations would manifest themselves through biology, sensory experience, logic, communication, even possible aesthetic solutions and the need or not for the equivalent of art, is unknowable. Additionally, one has to attempt to imagine the unimaginable while confronting another impossibility: removing our inherent anthropomorphism from the imaginative process. This problem is so interesting in the extreme “outside-the-box” perspective it requires, that every possible human bias we may unknowingly apply to the problem must be vigorously challenged. Nothing can be assumed, not vision or sound, nor even the way a question would be asked, so tied are our cognitive capabilities to the particular evolutionary structure of our brains. To look up to the eerily silent stars, is to look inward to our own being. But part of the beauty of this dilemma is that in the act of imagining the non-human through the lens of the human mind, we reveal shadows of our own identities to each other. This process also becomes a deep meditation on the act of communication itself, requiring us to parse not just the structural side of communication, but the intellectual and emotional reasons as to why we communicate at all. To simplify it to its core, what do artists do all day? We build signs and signals in various formats, embed them with nuanced meaning, and send them out into a world with zero guarantees of ever being seen, let alone unambiguously interpreted or understood. In short, there is a type of poetic “hope-with-no-guarantee” that defines much of our great art and which, I feel, SETI also grapples with. And also like SETI, one of art’s strengths is to embody this spirit not as an exercise in futility, but as one of our greatest human qualities. We are yearning, curiosity-seekers with great perseverance over time; if any problem requires us to remember this about ourselves, it is this one. Question Three: One of the primary concerns of sending a message into space, as emphatically expressed by Stephen Hawking, is that attracting alien attention could ultimately lead to the demise of the human race. Elon Musk recently stated that “intentionally signaling other civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy raises concerns from all the people of Earth, about both the message and the consequences of contact. A worldwide scientific, political and humanitarian discussion must occur before any message is sent.” Do you think the moral, ethical, or humanitarian concerns about the responsibility of interstellar messaging are justified? I whole-heartedly agree that interstellar messaging should be challenged on all these grounds. It is a rare class of problems where one decision made by a few in one era, could have global consequences on a generation of people far removed from that time. Because of the distances and times required to send, search for, and potentially find interstellar/galactic signals, the notion of two-way back and forth in one human lifetime is highly unlikely. Like with environmental stewardship, nuclear weapons, or healthcare, we are making decisions that need to be weighed in their immediate self-interest and, more problematically, what we are handing down many generations from now. With that said, I have always found Hawking and Musk’s position to be as hardline in its approach as the idea of 24-hour, all power, all frequency broadcasting. If these are the two poles of approaches, extreme silence or extreme signaling, I am interested in challenging both to find out what compromise could lie in-between. Just what is the scientific justification, as Hawking and Musk would propose, that we should remain silent, perhaps even hide our technological signals? This is a major point to challenge as Hawking has dominated the public discussion on the matter with his consistent use of a 500-year-old human example of Columbus’ first contact scenario with Native Americans. Why is this position so successful with the general public? Why does it feel intuitively correct to so deeply fear and assume the worst of the “other” even if it is off planet and we have no evidence to support that fear because we have never had such an encounter? Although there is a great deal of anthropological evidence of first contact scenarios on our own planet, there has never been a systematic study that could determine patterns or trends over time about the various ways humans have responded in those moments. For example, is Hawking suggesting that humans, across time and cultures, always had, and always will in the future, behave exactly as the Spanish did in 1492? Even if there were trends we discovered, certainly it would still be pure speculation to apply these trends to an unknown, probably significantlyolder non-human intelligence that has itself had to figure out how to cooperate and survive long-term. Just as vigorously, I want to know what is the justification that encoding and representing altruism is the reasonable first position to take in message design? Are there biological or strategic advantages to being the first to initiate altruistic behavior rather than fear and aggression? The optimists within the active messaging debate greatly rely on the premise that a ten or hundred thousand, even million-year-old civilization would have had to culturally, perhaps genetically, further evolve altruism and cooperation to an as yet unknown level for such long-term survival; and that it’s more likely “first contact” will be with a cooperative or benign intelligence. Just as I questioned the validity of applying human competitive and colonization behavior to an unknown intelligence, I am also intrigued to think through if and how we could apply our knowledge of biological and bio-cultural altruism off-planet. And from the creative content side of message construction, if altruism were an expected outcome of an advancing intelligence, how would we develop the adequate vocabulary (texts, concepts, images, sound, or something else entirely) to convey this commonality? I’m not underplaying the deep concern raised in Hawking or Musk’s position, only that, as I mentioned earlier, we can learn much about ourselves through the lens of interstellar contact. There needs to be much more work done on the matter before we take such a hardline approach of silence or pure altruism as we move into an age of possible interplanetary citizenship. Once again, I would argue that artists are crucial to these conversations as they have much to say about questions of the common good, pragmatic cooperation, the ethics of diversity and representation, altruism and the construction of symbols and objects embedded with the signs of our humanity. Image details clockwise from top left: